A month ago, I became the unwilling subject of my own cybersecurity nightmare. My car, a Mercedes-Benz GLC, vanished in the dead of night, not with a smash and grab, but with a silent, digital theft. As a cybersecurity journalist with 18 years in the field, I’ve written extensively about car hacking, even interviewing cybersecurity luminaries. Yet, like many, I’d fallen into the trap of believing “it won’t happen to me.” This personal experience shattered that illusion, thrusting me into the stark reality of modern car theft and the unsettling ease with which it can be executed, sometimes with tools that resemble a “Blocky Cars Online Hack Tool” in their simplicity and effectiveness.

This isn’t just my story; it’s a reflection of a growing trend. In the UK alone, a car is stolen roughly every eight minutes. Recent figures from the Office of National Statistics reveal a staggering 397,264 cars were stolen in England and Wales between October 2022 and September 2023. Land Rovers are the most targeted, with Mercedes and Ford following closely behind – a dubious podium finish for any automaker. Recovery rates are dismal, often below 20%. This isn’t about hotwiring and broken windows anymore. This is about sophisticated, often silent, digital intrusion.

My Mercedes GLC 220 AMG Line Premium D, equipped with keyless entry and start, became a statistic. Detectives informed me that six similar high-value cars were stolen within a mile radius over just two nights. The suspicion: an organized crime group, likely operating from major cities, targeting affluent areas.

Waking up to an empty driveway was surreal. Both car keys were in their usual place. No forced entry, no shattered glass – just an absence where my car should have been. My initial thought, as a cybersecurity professional, was immediate: my car had been hacked. But was it really “hacking” in the traditional sense, or something more akin to using a simplified “blocky cars online hack tool”?

Graham Cluley, of the Smashing Security podcast, confirmed my suspicion. “In its broadest sense, hacking is gaining unauthorized access. And that’s precisely what happened when thieves exploited a vulnerability in your car’s entry system.” David Rogers, CEO of Copper Horse, a connected car security specialist, concurred: “It’s almost certainly car hacking.” Many other experts I consulted echoed this sentiment.

However, Adam Pilton, a former police officer and detective now at CyberSmart, offered a nuanced perspective. “While ‘car hacking’ might evoke images of complex cyberattacks, the theft of six cars in a small area suggests a relay attack, a simpler yet highly effective method.” This raises a crucial question: is a relay attack, often executed with readily available tools that could be likened to a physical “blocky cars online hack tool,” truly a hack?

Ivan Reedman, Director of Secure Engineering at IOActive, injects a dose of realism. “If we define hacking as gaining unauthorized access to data in a system, then this might not strictly qualify as a hack. The criminals gained access to the car, but not necessarily to data. I’d argue it’s theft facilitated by technology, rather than pure hacking.”

Relay Attacks: The “Blocky Cars Online Hack Tool” of the Real World

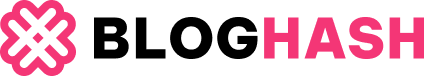

Despite differing opinions on the precise terminology, the consensus among eight cybersecurity experts I interviewed was clear: my car was stolen via a relay attack. My Mercedes featured “Passive Entry Passive Start” (PEPS). With the key nearby, I could enter and start the car without physically interacting with the key.

Chris Pritchard, from Lares cybersecurity consultancy, explained the mechanics. Thieves use “a tool and aerial to relay the signal between your key and the car. The car is fooled into thinking the key is close, unlocking the doors.” William Wright, CEO of Closed Door Security, elaborated: “Two devices are typically used. One near your house to intercept the key fob signal, even through walls, and another by the car to relay that signal.”

These relay devices need to be within just 10-15 meters of the key and the attack can be executed in as little as 30 seconds. Reedman adds, “The device closest to the key extends the key’s range, tricking the car into unlocking and starting. It’s a range extension attack, exploiting the PEPS system.”

Diagram illustrating the process of a relay attack on a keyless entry system.

Reedman, demonstrating the simplicity of this “blocky cars online hack tool” approach, even built a relay attack device using basic components: an audio amplifier, batteries, and copper wire. He successfully unlocked and started a Mercedes AMG for a BBC demonstration.

Once inside and driving, how did they keep the car going when the key signal was no longer present? Reedman clarifies, “Most vehicles, once started, will continue running even without key presence, though they may warn the driver. The engine will only stop when turned off manually. After that, they can use other methods, often involving the OBD port, to permanently bypass the need for your original key.” Cluley adds, “Stopping the engine mid-drive due to key absence would be dangerous, like if the key battery died. However, restarting after stopping is often prevented.”

OBD Access: Taking Control Beyond the Relay

The relay attack gets thieves into the car and driving, but to truly take control, they often need access to the on-board diagnostics (OBD) port. “OBD access allows starting the car using other devices,” Rogers explains. “Once the car is tricked into thinking there’s legitimate access, there’s no further obstacle to driving.”

Pritchard describes the OBD port’s role: “It’s typically under the steering wheel, used by mechanics for diagnostics. Criminals use OBD programming tools to add new keys.” He recounts a similar incident with his Audi, stolen for use in an armed robbery, where thieves used an OBD tool to program a new key. Key cloning, a more complex attack, was deemed unlikely by experts in my case.

Flipper Zero: Overhyped or Genuine Threat?

Initially, after sharing my experience online, some experts suggested a Flipper Zero attack might be involved. The Flipper Zero is a multi-tool device capable of various wireless signal manipulations, sometimes described as a “blocky cars online hack tool” for digital access. One online commenter suggested it could be used to “replicate the key inside the car, unlock it, and then duplicate the fob.” Another mentioned its potential for “recording rolling codes.”

A generic image of a car at night, symbolizing the vulnerability to theft.

However, experts interviewed for this article, with the full context, considered Flipper Zero involvement “highly improbable.” This aligns with Pritchard’s view: “Despite the Canadian government banning Flipper Zeros and claiming they are instrumental in auto theft, this isn’t a Flipper attack.” While Flipper Zeros are powerful tools for security testing and can exploit vulnerabilities in some systems, their role in sophisticated car theft, like relay attacks, is often overstated. Relay attacks rely on simpler, more readily available equipment, essentially a basic “blocky cars online hack tool” compared to the Flipper Zero’s broader capabilities.

Who Are the Perpetrators and How Do They Operate?

Having understood how my car was stolen, the question shifted to who and how they acquire these skills and tools. “The relay attack technique is widely known among car thieves, with ample online information,” Cluley stated.

Rogers emphasized the accessibility of car theft equipment: “It’s astonishingly easy to obtain. Most car thieves lack deep technical knowledge; they use pre-built tools, essentially a push-button “blocky cars online hack tool,” or wave an antenna.” The real expertise, he explained, lies higher up in the criminal supply chain, in those developing and distributing these tools.

Pilton added, “The tools themselves aren’t designed solely for car theft. They are often repurposed communication or signal extension devices. Like a crowbar, they’ve been adapted by criminals. The individuals carrying out the theft might just be using simple, pre-configured tools handed to them.”

Reedman reinforces the point about the low skill level required: “It requires minimal skill. They likely watch online videos and buy readily available relay equipment. It’s trivial.” He contrasts this with true hacking, which demands a higher level of technical expertise. Shockingly, reports indicate even children as young as 10 are involved in car theft, highlighting the accessibility and ease of these methods.

Manufacturer Response: A Mercedes Perspective

With keyless car theft on the rise, manufacturers face increasing pressure to enhance security. Wright argues, “The automotive industry lags behind others in technological attack protection.”

Mercedes-Benz, when contacted, stated, “Security is a top priority in our R&D.” A spokesperson mentioned that from mid-2019, the GLC facelift version incorporated a motion sensor in the key fob, deactivating the keyless GO function when stationary, thus preventing relay attacks. My 2018 model predated this upgrade. They also noted the option to manually disable KEYLESS GO and the GUARD 360° stolen vehicle help function via the Mercedes me app. However, they didn’t address why disabling KEYLESS GO isn’t more prominently offered to customers at purchase.

A Mercedes-Benz vehicle, representing the manufacturer’s perspective on security.

Shifting Blame and Shared Responsibility

Pritchard argues, “Car manufacturers prioritize ease-of-use over security.” He points to Range Rover thefts and the subsequent need for JLR to offer its own insurance due to unaffordable premiums. Rogers criticizes manufacturers’ slow response and tendency to blame victims, suggesting owners should have better key storage habits. He asserts, “The negligence lies with the manufacturer. They are aware of the issue but often inactive.” However, he acknowledges manufacturers are also victims of organized crime, emphasizing the need for international law enforcement action.

Manufacturers are implementing some improvements, such as motion sensors in key fobs and ‘time of flight’ technology to verify key proximity. Making car owners aware of keyless entry risks at the point of sale is crucial, allowing informed decisions about security versus convenience. Pilton advocates for shared responsibility, calling for collaboration between manufacturers, software developers, and regulators to establish minimum security standards and empower car owners.

The Criminal Justice Bill: A Step Forward, But With Concerns

The UK’s Criminal Justice Bill, introduced in November 2023, aims to criminalize possession of electronic devices used for vehicle theft. This includes signal jammers and similar tools, effectively targeting the “blocky cars online hack tool” market used in car theft. However, Rogers raises concerns about its impact on security research, potentially hindering legitimate research aimed at preventing theft and finding security flaws due to the risk of arrest for possessing these technologies for research purposes.

The Allure of “Dumb Cars” and the Scale of the Problem

Relay attacks target the “low-hanging fruit”—keyless entry cars. The attack is clean, silent, and leaves no trace, making it a low-risk, high-reward crime. Pritchard notes, “It’s a low-risk crime causing no vehicle damage, preserving resale value for criminals.” Pilton adds, “Keyless entry offers convenience but increases vulnerability to specific attacks.”

Cluley concludes he’s “very glad to have a dumb car,” highlighting a growing sentiment among security-conscious individuals. My own social media post about the theft was met with numerous similar stories, underscoring the widespread nature of this problem. Recovery and prosecution rates remain low, compounding the frustration.

Prosecution Challenges and Securing Your Keyless Car

Wright laments the “very poor” success rates in prosecuting relay attack car thefts. Cars are often quickly moved out of the country or dismantled in chop shops. Rogers points to occasional successes in intercepting stolen cars in containers or chop shops but emphasizes the need to target the international criminal tool manufacturing networks.

Pilton, from his law enforcement experience, acknowledges the challenges in identifying and prosecuting perpetrators, even when cars are recovered. He highlights the importance of organized crime groups leaving “breadcrumbs” that allow law enforcement to build a larger picture and take targeted action.

After a month, my car and the others stolen around the same time remain missing. The detective suspects mine might have been used for ATM ram-raiding, or it could be overseas or in parts by now. Recovery is unlikely, and even if it were, it belongs to the insurance company. Hope for answers and prosecution remains, but realistically, it’s a slim hope.

In the aftermath, I sought advice from experts on securing keyless cars. The unanimous recommendation: Faraday protection. “Use a Faraday box or wallet to block key signals,” advises Cluley, for both your main and spare keys. Reedman suggests testing Faraday effectiveness by attempting to unlock your car with the keys inside the Faraday enclosure. He also cautions that not all Faraday products are equally effective.

Rogers recommends disabling keyless ignition if possible, using a mechanical steering lock, and considering an OBDII port lock. Pilton highlights the value of social media in raising awareness.

Dan Bulman of KEYSHIELD introduced a new device: a sleeve that disables the key fob battery when stationary using motion sensor technology. While promising “100% protection,” my initial test resulted in the device working too well, preventing even legitimate access to my new car and triggering the alarm. Further investigation is needed.

For my new car, I’m adopting a “belt and braces” approach: a Faraday box and a steering wheel lock. My cybersecurity cynicism, once dormant regarding my own car security, is now fully reactivated.

This personal ordeal underscores a critical message: car manufacturers must move beyond prioritizing convenience and actively educate owners about the security vulnerabilities of keyless systems and the available protective measures. Until then, sharing stories and raising awareness, like this account of my “blocky cars online hack tool” experience, is crucial to empower car owners and push for greater automotive security.