Background

The global rise in life expectancy has led to a significant increase in the population of older adults with complex health needs. Geriatrics, as a specialized field of medicine, has emerged to address the unique healthcare requirements of this demographic, focusing on maintaining functionality and autonomy in the face of multimorbidity. The effectiveness of geriatric care models, which typically include comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), interdisciplinary teamwork, and tailored interventions, is well-documented. However, specialized geriatric treatment often requires more resources, including longer hospital stays and increased staffing. Consequently, it is crucial to identify patients who would most benefit from this specialized care, ensuring efficient allocation of healthcare resources.

The Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) tool, and its revised version ISAR-R, were developed to screen older patients at risk of adverse health outcomes, particularly in emergency department settings. These tools effectively identify high-risk seniors. However, studies in Germany have shown that ISAR can flag a large proportion of older patients as high-risk, with positive screening rates ranging from 58% in general internal medicine settings to 80% in emergency departments for patients over 70 or 75 years. This high sensitivity raises concerns about the suitability of ISAR for allocating patients to specialized geriatric hospital wards, as it may not be selective enough in identifying those who truly require this level of care.

Currently, there is a lack of clear, operationalized criteria for determining which older patients should be admitted to specialized geriatric hospital wards. Allocation decisions often rely on individual geriatric expertise, which can be subjective and inconsistent. This highlights the need for objective instruments to aid in the appropriate allocation of geriatric care resources.

The Standardized Evaluation and Intervention for Seniors at Risk (SEISAR) screening tool has emerged as a promising instrument in this context. SEISAR is designed to identify a wide range of deficits common in older adults and, importantly, classifies these problems as “absent,” “present, but compensated,” or “present, but uncompensated.” This distinction between compensated and uncompensated problems is a novel and potentially valuable feature for assessing the needs of geriatric patients. Originally, SEISAR was intended for use in emergency departments to identify patients with post-discharge geriatric outpatient care needs. Interventions were then planned for uncompensated problems either in the ER or in outpatient follow-up. However, the original SEISAR framework did not directly link uncompensated problems to inpatient geriatric care. In contrast, this study aimed to explore the use of SEISAR to characterize older patients admitted to specialized geriatric hospital wards and to evaluate its practicality and usability in this setting. Furthermore, the research investigated the potential impact of these geriatric problems on functional recovery during hospitalization.

Methods

The SEISAR screening tool encompasses 22 deficit areas across ten domains: communication, cognition, nutrition, mobility, activities of daily living (ADL), medication, behavior and affect, active medical issues, pain management, and social life. It also gathers data on the information source and living arrangements.

To ensure cultural and linguistic relevance for a German-speaking population, the original English version of SEISAR underwent a rigorous translation process. Three independent specialists in geriatric medicine translated the tool into German. The translated versions were harmonized, and subsequently, a non-medical native English speaker performed a back-translation to verify the accuracy and conceptual equivalence of the German version to the original English tool. This back-translation process identified no significant discrepancies.

Following translation, eight acute care geriatric hospital departments in Germany participated in a study to assess the practical application of the German SEISAR version. Participating departments used the tool to evaluate all consecutive patients admitted over a one-month period between December 2019 and May 2020. The SEISAR assessment was conducted upon admission and completed anonymously, without collecting identifiable patient data. The SEISAR manual (version 3.1) was provided to all participating sites to ensure standardized application. The assessments were performed by the attending physician under the supervision of the chief geriatrician, in conjunction with routine geriatric assessments typically carried out by nursing staff and physiotherapists. It is important to note that while nursing and physiotherapy staff were not actively blinded to the SEISAR results, they did not have access to or utilize these results in their routine assessments.

The SEISAR manual defines an “uncompensated problem” as a condition that is either newly возникшее or not adequately controlled, lacking effective coping mechanisms or strategies.

In addition to the SEISAR assessment, data were collected on patients’ admission source, length of hospital stay, whether early rehabilitation procedures were performed, and Barthel Index (BI) scores at admission and discharge. The German version of the BI ranges from 0 (complete dependence) to 100 (complete independence in ADL). Early rehabilitation in the German healthcare system is a standardized, coded procedure involving a minimum duration, specific assessment content, and therapeutic sessions, allowing for reimbursement of multi-professional geriatric care costs.

Statistics and Ethics

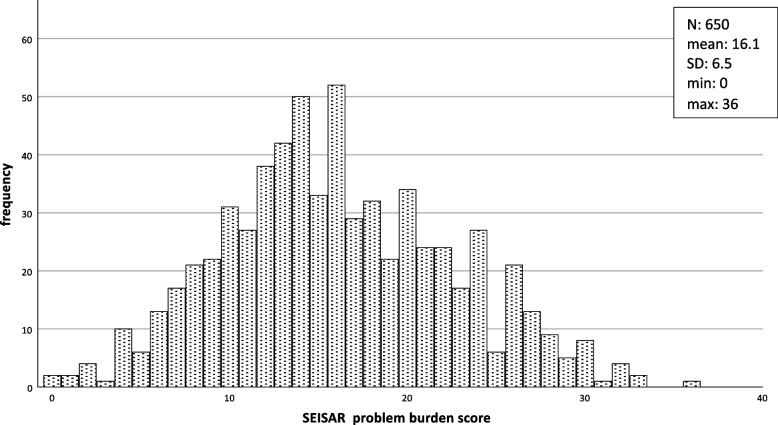

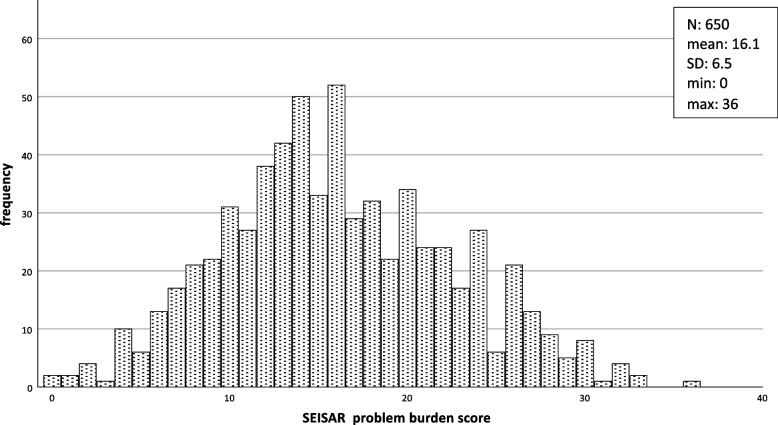

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corp, Version 29, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviations (SDs), minimum (min) and maximum (max) values, or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables are presented as absolute numbers and percentages (n, %). Beyond descriptive statistics of problem prevalence and count, a problem burden score was calculated for each patient, assigning 0 points for “problem absent,” 1 point for “compensated problem,” and 2 points for “uncompensated problem,” with a maximum possible score of 44 points.

For group comparisons, the change in BI score (discharge BI minus admission BI) was calculated and categorized as “decline or no change” versus “increase of ≥ 5 points.” Unpaired t-tests were used to analyze differences in the frequency of problems between these two groups. Chi-square tests were conducted for items with ≥ 15% differences in uncompensated problems between groups. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare BI scores, BI changes, and admission type (direct admission from general practitioner or emergency department vs. transfer from other hospital or department). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethics committee of Ruhr University Bochum (Nr. 20-6916-BR, approved 27.04.2020). The ethics committee waived the need for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study. All methods adhered to relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Data were collected from 756 patients admitted to eight geriatric hospital departments across six German federal states. A majority of patients (78%) resided in their own homes or apartments prior to hospitalization. Over half (56%) lived alone, while 34% lived with a spouse or family. The primary admission sources were transfers from other hospital departments (64%), direct admissions from emergency departments (19%), and referrals from general practitioners (15%). The median length of hospital stay was 16 days (IQR 14–20). Detailed patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population (n = 756)

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Living situation | |

| Alone | 422 (55.8) |

| With spouse or family | 260 (34.4) |

| Residence with service | 29 (3.8) |

| Unknown | 45 (6.0) |

| Residential status | |

| House, apartment | 593 (78.4) |

| Nursing home, group home | 64 (8.5) |

| Residence without service | 28 (2.4) |

| Unknown | 81 (10.7) |

| Admission from | |

| Admission from emergency department | 145 (19.2) |

| Referral from general practitioner | 111 (14.7) |

| Transfer from other hospital department | 480 (63.5) |

| Unknown | 20 (2.6) |

| Duration of early rehabilitation procedure | |

| 55 (7.3) | |

| 7–13 days | 110 (14.6) |

| 14–21 days | 441 (58.3) |

| > 21 days | 149 (19.7) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.1) |

| median (IQR) | |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 16 (14–20) |

| Barthel-Index on admission (points) | 40 (30–55) |

| Barthel-Index at discharge (points) | 60 (45–75) |

| Increase of Barthel-index (points) | 15 (5–30) |

| mean ± SD | |

| Absent problems per patient | 11.6 ± 4.0 |

| Compensated problems per patient | 4.3 ± 3.6 |

| Uncompensated problems per patient | 5.9 ± 3.5 |

| SEISAR problem burden score (missing n = 106) | 16.1 ± 6.1 |

SD Standard deviation, IQR Interquartile ranges

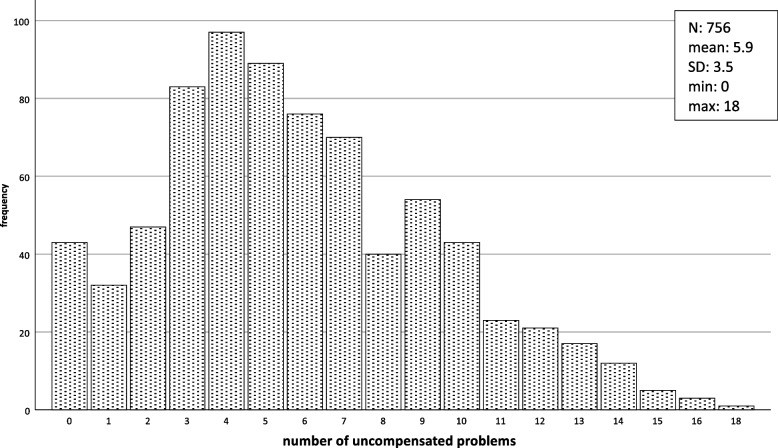

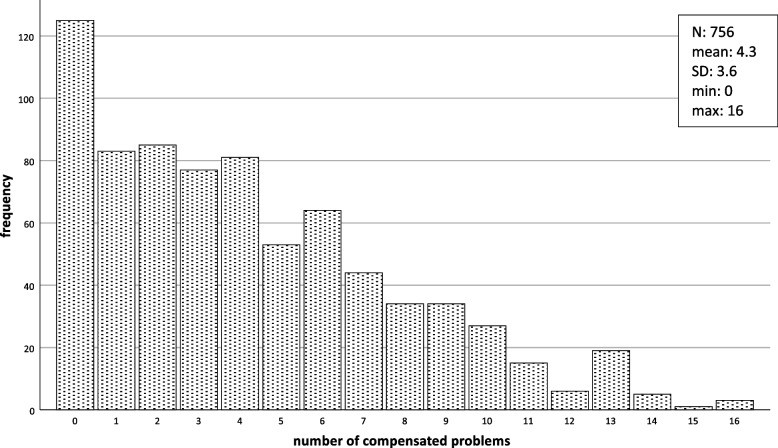

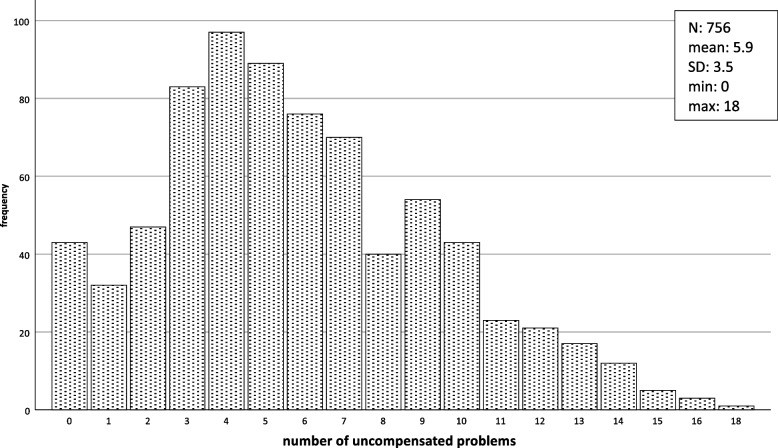

Across all patients, a total of 3,230 compensated problems and 4,425 uncompensated problems were identified, averaging 4.3 (± 3.6) compensated and 5.9 (± 3.5) uncompensated problems per patient. While a small percentage (5.7%) had no identified problems, the majority (90%) presented with a substantial number of uncompensated problems, ranging from 1.7 to 18.0 (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1. Frequency of compensated problems per patient (n = 756)

Fig. 2. Frequency of uncompensated problems per patient (n = 756)

The most prevalent uncompensated problems were polypharmacy (73%), falls (60%), persistent presenting symptoms (51%), mobility issues (problems walking, 49%), and active comorbidities (46%). In contrast, the most common compensated problems included impaired vision (54%), impaired hearing (36%), limitations with basic hygiene (33%), difficulties with meal preparation (32%), and mobility issues (problems walking, 29%) (Table 2). The mean SEISAR problem burden score was 16.1 (±6.1, min: 0, max: 36) (Fig. 3).

Table 2. Prevalence of problems absent, compensated or uncompensated (n = 756*)

| Problem Area | Absent (%) | Compensated (%) | Uncompensated (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication: | |||

| Impaired vision | 267 (35.8) | 402 (54.0) | 76 (10.2) |

| Impaired hearing | 374 (50.7) | 263 (35.6) | 101 (13.7) |

| Cognition: | |||

| Acute confusion/disorientation | 496 (66.0) | 60 (8.0) | 195 (26.0) |

| Undiagnosed cognitive problems | 576 (77.2) | 44 (5.9) | 126 (16.9) |

| Nutrition: | |||

| Recent weight loss/malnutrition | 431 (57.1) | 58 (7.7) | 266 (35.2) |

| Substance abuse | 708 (94.7) | 9 (1.2) | 31 (4.1) |

| Mobility: | |||

| Falls | 223 (29.6) | 81 (10.8) | 449 (59.6) |

| Problems walking/difficulty in using walking aid | 164 (21.9) | 216 (28.8) | 369 (49.3) |

| Activities of daily living: | |||

| Difficulties with meal preparation | 303 (40.4) | 242 (32.3) | 205 (27.3) |

| Limitations with basic hygiene | 296 (39.7) | 247 (33.2) | 202 (27.1) |

| Incontinence | 403 (53.9) | 184 (24.6) | 161 (21.5) |

| Medication: | |||

| Polypharmacy/new medication | 112 (14.9) | 91 (12.1) | 548 (73.0) |

| Prescription management difficulties | 456 (61.5) | 149 (20.1) | 136 (18.4) |

| Behavior/affect: | |||

| Depression | 627 (83.3) | 45 (6.0) | 81 (10.7) |

| Agitation | 690 (92.1) | 21 (2.8) | 38 (5.1) |

| Active medical issues: | |||

| Persistent presenting symptoms | 194 (25.8) | 175 (23.3) | 382 (50.9) |

| Active co-morbidities | 237 (31.6) | 171 (22.8) | 341 (45.5) |

| Pain management: | |||

| Persistent pain | 343 (45.5) | 186 (24.7) | 225 (29.8) |

| Joint/bone pain | 366 (48.7) | 177 (23.5) | 209 (27.8) |

| Social: | |||

| Insufficient support, lives alone | 330 (44.2) | 216 (29.0) | 200 (26.8) |

| Social isolation/neglect | 567 (76.3) | 128 (17.2) | 48 (6.5) |

| Previously refused service | 640 (86.4) | 65 (8.8) | 36 (4.8) |

*missing values in up to 2.7% of cases per group

Fig. 3. SEISAR problem burden score

SEISAR problem burden score (number of compensated (1 pt.) + number of uncompensated (2 pts.) problems. The problem burden score could only be calculated in n = 650 participants without any missing values

In 730 patients with both admission and discharge BI data, the median BI increase during hospitalization was 15 points. While most patients (72.9%) showed a BI increase of ≥ 5 points, a small percentage experienced a BI decrease (6.3%) or no change (11.6%).

Group comparisons revealed that patients who experienced an increase in BI during their geriatric hospital stay had a trend towards fewer uncompensated problems (mean 5.6 vs. 7.2; p = 0.06), although this difference was not statistically significant at the p<0.05 level. The number of compensated problems did not differ significantly between groups (mean 4.2 vs. 4.3; p = 0.73).

However, the SEISAR problem burden score was significantly lower in patients with BI improvement (mean 15.5 ± 6.3) compared to those without improvement (mean 19.0 ± 6.5; p < 0.001).

Specific uncompensated problems showing > 15% prevalence differences between groups (BI increase vs. no increase/decrease) included “acute confusion/disorientation,” “undiagnosed cognitive problems,” “problems walking/difficulty in using walking aid,” and “active co-morbidities” (Additional file 1). Chi-square tests confirmed significantly lower prevalence of these uncompensated problems in the BI improvement group.

Admission type (direct vs. transfer) did not significantly influence BI scores or BI gain during hospitalization.

Discussion

This study provides valuable insights into the spectrum and complexity of functional and health-related problems in patients admitted to acute care geriatric hospital units in Germany. The SEISAR tool effectively highlighted the multifaceted nature of these patients’ needs. The most prevalent uncompensated problems—polypharmacy, falls, mobility difficulties, persistent symptoms, and active comorbidities—underscore the critical areas requiring targeted intervention in this population. Similarly, the high prevalence of compensated problems like vision and hearing impairment, hygiene and meal preparation limitations, and pre-existing mobility issues, while managed, still contribute to the overall complexity of patient care. The prevalence of geriatric syndromes such as acute confusion (uncompensated in 26%) and malnutrition (uncompensated in 35%), although less frequent than other problems, further emphasizes the vulnerability of this patient group.

The average patient in this study, living independently before admission, presented with 4 compensated and 6 uncompensated problems, a low admission Barthel Index of 40, and a median hospital stay of 16 days, achieving a median BI increase of 15 points. This profile underscores the significant care needs and potential for functional improvement in patients admitted to specialized geriatric wards. The substantial variability in the number of problems per patient further highlights the heterogeneity of this population and the importance of individualized assessment and care planning.

The SEISAR problem burden score, combining compensated and uncompensated problems with differential weighting, emerges as a potentially useful metric for quantifying the overall geriatric complexity of patients. While this study did not compare SEISAR data with non-geriatric hospital populations, the problem burden score could potentially serve as a discriminatory tool to identify patients who would most benefit from specialized geriatric care. Future research comparing SEISAR scores between geriatric and non-geriatric settings is needed to validate this hypothesis.

Despite the detailed SEISAR manual, some ambiguities in classifying problems, particularly as “compensated” versus “uncompensated,” were noted. For instance, the criteria for classifying polypharmacy as compensated require further clarification. Is it compensated if the patient manages their medications independently, if a caregiver assists, or only if the medication regimen has been reviewed and optimized by a geriatrician? While the current manual is adequate for SEISAR’s original ER-based application, refining these definitions is crucial for its potential use in stratifying admission needs for acute geriatric wards. However, the overall feedback from participating physicians was positive, with SEISAR being perceived as easy and quick to administer after initial medical assessment. Concerns regarding classification uncertainties were infrequent.

This study has limitations. Data collection by attending physicians, rather than dedicated research staff, may have led to underreporting of problems. However, this approach reflects real-world clinical application of SEISAR. The absence of age and gender data limits further subgroup analyses. Future studies should include these demographic variables. The study also did not track changes in problem status (uncompensated to compensated) during hospitalization, which could provide insights into the impact of geriatric interventions. Crucially, the lack of a comparison group from non-geriatric hospital settings limits conclusions about SEISAR’s discriminatory power for allocating specialized geriatric care.

Conclusion

SEISAR is a valuable, brief, standardized comprehensive geriatric assessment tool for identifying compensated and uncompensated health problems in older adults. While initially designed for emergency department discharge planning, this study demonstrates its utility in characterizing patients within specialized geriatric hospital units, highlighting the high number, variability, and complexity of their geriatric needs. Further research is necessary to establish SEISAR’s objectivity, validity, and reliability specifically for acute geriatric hospital settings and to determine its effectiveness in differentiating patients requiring specialized geriatric care from those who can be appropriately managed in non-geriatric settings. Future studies should also address the refinement of problem classification criteria to enhance the tool’s precision and clinical utility as a functional assessment tool for geriatric patients in acute care.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Prevalence of problems by change in barthel-index.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Open Access Publication Funds of the Ruhr University Bochum.

Abbreviations

BI: Barthel-Index

IQR: Interquartile ranges

ISAR: Identification of Seniors at Risk-score

max: maximum

min: minimum

SD: Standard deviations

Authors’ contributions

The study was designed by RW and UT. The translation of the instrument was performed by RW, MD and MJ. Data were obtained by MJ, HF, MD, MMe, MMu, AZ and HJH. Statistical analysis and preparation of the manuscript were performed by UT and RW with significant contributions of JV. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the ethical committee of Ruhr University Bochum (Nr. 20-6916-BR approved on 27.04.2020). The need for informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of Ruhr University Bochum, because of the retrospective nature of the study. All methods used were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[1] Rubenstein LZ, Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland D. Impacts of geriatric evaluation and management programs on defined outcomes: overview of the evidence. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991 Nov;39(11 Pt 2):8S-16S.

[2] Stuck AE, Siu AL, Wieland GD, Rubenstein LZ, Michel P. Comprehensive geriatric assessment: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Lancet. 1993 Oct 23;342(8878):1032-6.

[3] McCusker J, Bellavance F, Cardin S, Trepanier S, Verdon J, Primeau F, Ahmarani T. Detection of older people at increased risk of adverse health outcomes after an emergency visit: the ISAR screening tool. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999 Dec;47(12):1552-62.

[4] McCusker J, Verdon J, Tousignant P, de Courval FP, Dendukuri N, Belzile E. Rapid risk screening for older adults in the emergency department: the revised Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR-R). J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006 Jun;61(6):618-24.

[5] Purser JL, Weinberger M, Cohen HJ, Divine GW, Smith DM, আজিজ AA, Goodwin JS. Performance of a brief screening tool to predict hospital admission and functional decline in older adults in the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Aug;49(8):1001-7.

[6] Gillmann G, Krummhaar C, Weyerer S, Wagner M, Bachmann C, Pfeifer-Tiller M, Eisele M, Konig HH, Luck T. Risk of re-hospitalisation or death is high in older medical patients identified as high-risk by the Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) screening tool: a prospective observational study. BMC Geriatr. 2014 Jul 23;14:88.

[7] Graf C, Buhrmann C, Bottcher HD, Nowak A, Jessen F, Luck T, Muhlmann M, Wagner M, Weyerer S, Konig HH, Eisele M. Screening for geriatric patients at risk for adverse outcomes in the emergency department. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2017 Dec;50(8):677-681.

[8] Schmidt-Weitmann S, Sieber CC, Gaßmann KG, Volkert J, Dassen T, Beckmann A, Freiberger E, Hantikainen V, Heider D, Hoffmann W, et al. Development of a standardized procedure for the risk assessment of elderly patients in the emergency department: Standardized Evaluation and Intervention for Seniors at Risk (SEISAR). Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2017 Dec;50(8):669-676.

[9] Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965 Feb;14:61-5.

[10] Becker C, Nikolaus T, von Renteln-Kruse W, Wetzel R, Donner-Banzhoff N, Hoffmann F. Characteristics of geriatric patients in different healthcare settings in Germany: baseline results of the ActiGap cluster randomized controlled trial. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2019 Feb;52(1):35-41.

[11] von Renteln-Kruse W, Rohrmann S, Bremer M, Frohlich L, Kohler M, Muhlberg W, Ruther E, Sandholzer H, Sieber CC, Vogelsmeier A, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient geriatric rehabilitation: results of a prospective multicenter study. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2010 Dec;43(6):381-90.

[12] von Renteln-Kruse W, Wilken B, Christ M. Acute geriatric patients in internal medicine: spectrum of diseases, comorbidities and functional status. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2006 Dec;39(6):434-40.

[13] Vollaard AM, Petri H, Obermann M, Wolf KH, von Renteln-Kruse W. Impact of sarcopenia and frailty on functional outcome after inpatient geriatric rehabilitation. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2023 Feb;56(1):33-39.

Associated Data

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Prevalence of problems by change in barthel-index.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.