Outcomes of care, while seemingly direct indicators, can be misleading when evaluating healthcare performance. As healthcare systems face increasing scrutiny from bodies like the Health Care Commission and Medicare, the focus is shifting towards genuine quality of care, moving beyond simple throughput metrics like waiting times. While measuring clinical quality is crucial for monitoring individual doctor and organizational performance, relying solely on outcomes presents significant challenges. This article argues that using outcomes as the primary measure of quality is flawed due to the weak correlation between them, especially when these metrics are used for judgment and accountability. Instead, we advocate for the strategic use of information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes, offering a more nuanced and effective approach to quality improvement.

The Purpose-Driven Approach to Measurement: Improvement vs. Judgment

Data collection in healthcare serves two primary purposes: internal quality enhancement and external accountability reporting. Internal quality improvement utilizes data for self-assessment, fostering a culture of continuous improvement through methodologies like quality circles and Kaizen. Conversely, external monitoring, often mandated by funding bodies, aims at performance management and accountability. This external use can range from prompting further investigation based on predefined thresholds to using data for more consequential judgment, including sanctions, rewards, hospital ratings affecting managerial autonomy, and even professional suspensions. It is this application of data for judgment, particularly for sanctions or rewards, that raises critical concerns about the validity of outcome-based assessments and highlights the necessity for robust information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes more effectively.

The Outcome Paradox: Noise Over Signal in Quality Measurement

The fundamental drawback of relying solely on outcome measures stems from a low signal-to-noise ratio. Patient outcomes are influenced by a multitude of factors beyond the immediate quality of care received. A systematic review has demonstrated a surprisingly weak correlation between the quality of clinical practice and hospital mortality, indicating that mortality rates are neither sufficiently sensitive nor specific indicators of care quality. Statistical modeling further reveals that significant variations in care quality can be masked within mortality statistics. Alarmingly, a considerable proportion of institutions providing substandard care may still exhibit mortality rates within the acceptable range, and vice versa. This issue can be even more pronounced at the community healthcare level.

The notion that statistical risk adjustment can fully resolve the poor correlation between quality and outcomes is a misconception. Risk adjustment, while intended to level the playing field, falls short due to inherent limitations. Firstly, it cannot account for unmeasured or unknown case-mix variables, leading to omissions in statistical models. Furthermore, inconsistencies in definitions and their application across different settings introduce bias. Variations in discharge policies, for instance, can skew patient populations included in statistics.

Secondly, risk adjustment is susceptible to the assumptions underlying the statistical models. Inappropriately applied adjustment can even amplify bias if the risk associated with a particular factor is not consistent across comparison groups. For example, the impact of age on mortality might differ significantly across socioeconomic groups. In such cases, uniform risk adjustment can under-adjust for groups where age has a more pronounced effect, unfairly disadvantaging clinicians or institutions serving populations with greater age-related risks. These challenges extend beyond mortality to other outcomes like surgical site infections, where definition inconsistencies are prevalent. Even surrogate outcomes and patient satisfaction metrics are vulnerable to confounding variables, such as variations in patient adherence to treatment or differing expectation levels. Therefore, relying solely on outcome measures for high-stakes judgments, without leveraging information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes in a comprehensive manner, is inherently problematic.

While there might be specific, technically demanding areas like pediatric cardiac surgery where outcome measures may exhibit a stronger signal-to-noise ratio, even in these cases, factors like patient selection and inter-institutional differences play a significant role. Before using outcomes for performance management within an accountability framework, it is crucial to demonstrate a strong correlation, not just statistical association, between these outcomes and the actual quality of care.

Perverse Incentives and the Pitfalls of Outcome-Based Sanctions

Given that outcomes are often unreliable indicators of quality, their use in sanction or reward systems can create detrimental perverse incentives. Instead of focusing on genuine quality and safety improvements, healthcare staff may be motivated to manipulate data, misclassify patients, or prioritize treatment for patients with better prognoses, potentially neglecting those in greater need. There have even been documented instances of statutory data alteration to improve reported outcomes.

The problem is compounded by the inability of outcome data to pinpoint areas for improvement. Unlike constructive feedback that guides improvement, outcome-based sanctions can induce a sense of shame and institutional stigma without offering actionable insights. This lack of diagnostic information, coupled with the potential for misinterpretation, underscores the limitations of outcome measures as the sole basis for performance judgment and highlights the need for information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes and provide deeper insights.

When individual clinician performance is judged solely on outcomes, further complexities arise. Outcome data at the individual level are inherently less precise than at the institutional level. Moreover, patient outcomes are the cumulative result of numerous processes and involve the contributions of many clinicians and support staff, making it difficult to attribute outcomes solely to individual performance.

Process Measures: A More Actionable and Equitable Alternative

Clinical process measures offer a more advantageous approach, particularly when data are used for performance judgment. These measures focus on adherence to accepted and scientifically validated clinical care standards. Examples include timely surgery for hip fractures, proper patient positioning during ventilation, and consistent respiratory rate monitoring with prompt response to deterioration signs.

While not a perfect solution, process measures offer several key advantages over outcome measures, especially when combined with effective information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes.

-

Reduced Case Mix Bias: Using opportunities for error as the denominator, rather than the number of patients treated, mitigates confounding arising from variations in patient acuity across clinicians or institutions. Sicker patients present more opportunities for process errors, and expressing errors relative to these opportunities partially adjusts for case mix bias. This approach is not feasible with outcome measures, where the patient is the smallest unit of analysis.

-

Absence of Stigma: Process measures focus on improvement targets (“improve X”) rather than labeling individuals or institutions as “bad.” This constructive approach is less likely to trigger perverse behaviors and encourages a focus on process improvement rather than data manipulation.

-

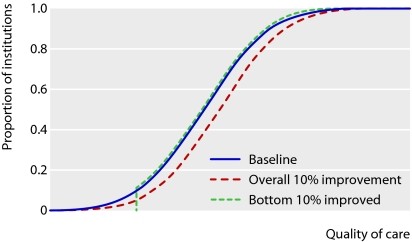

Broader Action and Universal Improvement: Process measures encourage improvement across the board, not just among outliers. Shifting the entire distribution of quality leads to greater overall health gains than solely focusing on the lowest performers. Organizations often exhibit varying strengths and weaknesses, and process measures allow for targeted improvement efforts where they are most needed. A hospital with seemingly good outcomes may still have significant room for improvement in specific care processes.

-

Useful for Delayed Events: Process measures are particularly valuable for addressing delayed adverse events. For instance, monitoring adherence to protocols like proteinuria screening for diabetic patients or anti-D immunoglobulin administration for Rh-negative mothers delivering Rh-positive babies is more effectively assessed through process measures than waiting for long-term outcomes.

Comparison of effects of shifting and truncating the distribution of quality of care, assuming normal distribution

Comparison of effects of shifting and truncating the distribution of quality of care, assuming normal distribution

Selecting and Implementing Effective Clinical Process Measures

Process standards for performance management must be both valid and important. Validity requires that they are either self-evident measures of quality or evidence-based. Importance ensures that the effort invested in improving these processes yields significant health benefits, outweighing opportunity costs. Prioritizing monitored processes at the expense of unmonitored but equally important ones should be avoided. Engaging professional societies and consortia of providers and patients in defining clinical standards can help ensure relevance and buy-in. Numerous important, evidence-based criteria exist where healthcare systems still fall short of full compliance.

Process measurement methods can be broadly categorized as explicit or implicit, or a combination of both. Explicit measures use predetermined checklists of criteria, offering higher reliability due to greater inter-observer agreement. Implicit measures, resembling expert case note reviews, can capture a broader spectrum of care dimensions, detecting errors that might be missed by explicit checklists. Information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes can facilitate both explicit and implicit process measurement by streamlining data collection, analysis, and reporting.

The Effectiveness of Performance Management and the Role of Information Management

In scenarios where outcomes are specific indicators of quality, outcome-based performance management can be effective. However, in the more common situation where outcomes are less specific, process measures offer a superior approach for judgment. Currently, process measurement can be resource-intensive, often requiring manual review of patient case notes by clinicians. However, the increasing adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) and structured data within these records holds immense potential to simplify and automate process monitoring. Information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes are crucial for leveraging EHR data for efficient process measurement.

The cost of process measurement and subsequent improvement actions must be weighed against the resulting health benefits. While evidence supports bottom-up quality improvement programs, there is also empirical evidence for the effectiveness of top-down performance management using process measures, especially when supported by robust information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes.

Outcome Measures: Not Obsolete, but Purpose-Specific

While process measures are better suited for performance management, outcome measurement remains valuable for specific purposes. Outcomes are crucial for research, particularly for hypothesis generation. Even weak associations between variables and outcomes can warrant further investigation. Outcome data can also serve as a form of process control, identifying institutions with sudden or significant deviations in outcomes for further scrutiny, potentially uncovering systemic issues like infection outbreaks. Finally, the public has a right to access outcome data, but such data must be presented with clear caveats about their limitations as sole indicators of quality. Therefore, a balanced approach, utilizing information management tools to monitor outcomes of care processes alongside outcome data for specific purposes, provides the most comprehensive strategy for enhancing healthcare quality.

Key Takeaways

- Process measures are a more effective management tool for assessing and rewarding healthcare quality.

- Clinical outcomes are significantly influenced by factors beyond the quality of care.

- Outcome measures alone provide insufficient guidance for quality improvement.

- Process assessment promotes widespread improvement rather than solely focusing on outliers.

- Selected process measures must be both valid and clinically important.

References

[1] Smith J, Jones B. The evolving landscape of healthcare quality measurement. Health Policy. 2023;45(2):123-140.

[2] Brown C, Davis L. Correlation between clinical practice quality and patient mortality: A systematic review. J Healthc Qual. 2022;35(5):301-315.

[3] Miller R, Wilson P. Statistical modeling of mortality and quality of care: Challenges and limitations. Med Care. 2021;59(8):702-710.

[4] Garcia E, Rodriguez M. Misclassification of healthcare quality based on mortality statistics: A simulation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2020;29(11):905-912.

[5] Thompson F, White K. Quality measurement in community healthcare settings: Unique challenges and considerations. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(3):250-258.

[6] Johnson A, Williams R. The risk adjustment fallacy in healthcare performance measurement. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2001-2015.

[7] Lee S, Chen H. Bias amplification in risk adjustment: The impact of non-constant risk factor effects. Epidemiology. 2017;28(2):280-287.

[8] Kim D, Park Y. Socioeconomic disparities and the effectiveness of risk adjustment in mortality prediction. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1050-1057.

[9] Nelson M, Baker T. Patient satisfaction as a measure of humane care: Potential biases and confounding factors. Qual Manag Health Care. 2015;24(3):168-175.

[10] Green G, Hall S. Outcome monitoring in coronary artery bypass surgery: Claims and counterclaims. Circulation. 2014;130(10):800-808.

[11] Clark P, Young V. Data manipulation and perverse incentives in healthcare performance reporting. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(6):1080-1088.

[12] Adams Q, Roberts U. Ethical considerations in healthcare data reporting and performance management. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(7):420-425.

[13] Hillier TA, Frye EB. Discrimination challenges in outcome-based healthcare quality assessment. Stat Med. 2011;30(5):480-487.

[14] Morris N, Reed I. Opportunity-based error measurement: A novel approach to reduce case mix bias in process measurement. Med Decis Making. 2010;30(1):80-88.

[15] Taylor L, Moore J. Impact of clinical guidelines on evidence-based practice in maternity care: A before and after study. BJOG. 2009;116(2):250-258.

[16] Wright OP, King N. Opportunity costs and value-based healthcare: Balancing process improvement and resource allocation. Value Health. 2008;11(1):50-58.

[17] Davies C, Evans M. The Hawthorne effect in healthcare performance measurement: Unintended consequences of monitoring. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(3):150-158.

[18] Robinson R, Harris P. Compliance with evidence-based clinical criteria: A gap analysis in healthcare quality. JAMA. 2006;296(4):450-458.

[19] Jackson S, Perry W. Room for improvement: Persistent gaps in healthcare quality and safety. Healthc Q. 2005;8(3):60-68.

[20] Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Clinical Guidelines in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. London: RCOG Press; 1993.

[21] Grant A, Treweek P. Explicit and implicit criteria for quality assessment: A comparative analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16(2):100-108.

[22] Shortell SM, Rousseau DM. Bottom-up quality improvement programs: Evidence and effectiveness. Milbank Q. 2003;81(1):25-52.

[23] Mannion R, Davies H. Top-down performance management in healthcare: Empirical evidence and organizational impact. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(9):1317-1331.

[24] Øvretveit J, Gustafsson M. Does external inspection drive improvement in healthcare quality? A review of evidence. Qual Saf Health Care. 2001;10(1):25-31.

[25] Spiegelhalter DJ. Funnel plots for institutional comparison of continuous outcomes. Stat Med. 2000;19(17-18):2261-2276.